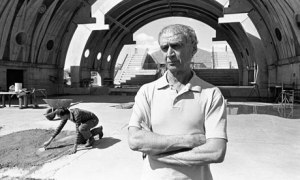

Image of Paolo Soleri at Arcosanti

(http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/apr/10/paolo-soleri-architect-dies-93)

“Our throw-away culture has made obsolescence the measure of its dynamism… The pernicious effect of planned obsolescence is the erosion of excellence.” – Paolo Soleri

The 1950s was a decade that experienced economic growth with the increase in manufacturing and home construction. The idea of “The American Dream” plagued almost every family’s mind. This idea suggested that everyone should own their home, have their own pastoral landscape in the form of a front or back yard, own motor vehicles, and live outside of the city near their strip malls. This idea was implemented nation-wide and further enforced by the American Highway Act of 1956. This created networks of highways across the United States and allowed people to settle further away from the city center. The consequence of this was that architecture started becoming temporary and known as “throw away architecture” to some. As people moved further outside of the city to have their own “American Dream,” buildings in the city center became obsolete, were destroyed, and rebuilt as something else. This waste of materials and resources was what one Italian man from Turin wanted to avoid.

“Unless we moderate, unless we reinvent the American dream, then it’s not going to be a dream. It’s going to be doomsday.” – Paolo Soleri

Paolo Soleri was born in Turin, Italy on June 21st, 1919. He was educated in architecture at the Polytechnic University of Turin, where he graduated with a PhD degree with the highest honors. In 1946, he started a year and a half fellowship under Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin West. Here, he gained an interest in urban architecture and the environment (“Soleri”, p.9). The two architects could not have been more different. Wright’s buildings sprawl; Soleri’s ascend. Wright’s homes work best in suburbs; Soleri was already beginning to imagine compact cities where cars would be unnecessary and people would live, literally, right on top of each other. There would be no suburbs. He studied Wright’s plans of Broadacre City and noticed that the utopic city Wright was proposing, further emphasized the promotion of urban sprawl. Soleri’s later designs would show a rigorous intent to dispose of urban sprawl, among other issues that were starting to surface in the 1950s.

Frank Lloyd Wright and Broadacre City Model

(http://www.angelfire.com/crazy3/kamica/images/BROACRE_FRANK.JPG)

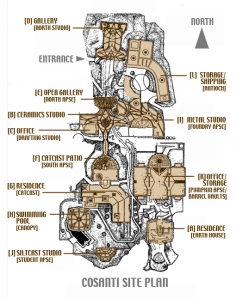

In 1956 he settled in Scottsdale, AZ where he founded the housing and workshop complex of Cosanti. Here he developed his bronze bells as a means of income. He also discovered the technology of silt casting. This was the method where concrete shells would be poured into the ground, like his bells he was creating at the time, and then the land would be excavated once the concrete had cured. Many of the buildings on the complex were built below ground level and surrounded by mounds of earth. This type of construction acts as natural insulation for temperatures year round. The structures were also built as apses. The apse was used as a passive solar energy collector and was oriented to maximize or minimize solar exposure. South facing apses are used at Cosanti as year-round outdoor workspaces, providing sunny spaces in the winter and shady conditions in the summer heat due to the changing angle of the sun.

In response to the United States’ “throw-away culture” that was taking over many of the cities and which Soleri was very strongly against, Soleri developed a concept of how cities should be built called Arcology. The word Arcology came from combining the words architecture and ecology. An ecology, as defined by Mirriam-Webster Dictionary, is “a science that deals with the relationships between groups of living things and their environments” (http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ecology). If an ecology deals with how living things respond to their environments, Arcology deals with the relationship between humans and the built environment. “The arcology concept proposes a highly integrated and compact three-dimensional urban form that is the opposite of urban sprawl with its inherently wasteful consumption of land, energy resources and time, and tendency to isolate people from each other and the community. Miniaturization creates the Urban Effect, the complex interaction between diverse entities and individuals, which mark healthy systems both in the natural world and in every successful and culturally significant city in history” (http://arcosanti.org/theory/arcology/main.html). Some people claim that his inspiration for arcology comes from science fiction novels, though that may just be the assumptions of the writer. “Perhaps not so far-fetched, Soleri was intrigued by the futuristic novels of Jules Verne. The irony is that Soleri’s theories were so far ahead of their time, they might have seemed like premonitions to a general public that failed to believe in limited natural resources then, but realize differently now” (http://www.azcentral.com/news/articles/2010/08/22/20100822arcosanti-paolo-soleri.html).

Arcology reduced the city’s dependence on the automobile, which was consuming city land by using more than sixty percent of that land for roads and services. The multi-functional nature of arcological design would house residential, commercial, and public spaces all within easy access to each other. This would make walking the primary form of transportation in the cities. Because of an arcology’s direct proximity to uninhabited wilderness, the city dweller would also have constant immediate access to rural space. Agriculture would be able to be situated near the city, maximizing the efficiency of a local food distribution system. In terms of energy usage, Arcology would use passive solar architectural techniques such as the apse effect – seen in Cosanti –, greenhouse architecture and garment architecture to reduce the energy usage of the city for cooling, heating, and lighting. In response to the sprawl that was happening all over the United States, Soleri’s three dimensional cities would use energy and resources more efficiently than a conventional modern city. “Pollution is a direct function of wastefulness, not efficiency… Suburban sprawl mandates a hyper-production-consumption cycle and creates mountains of waste and pollutants” (http://arcosanti.org/theory/arcology/main.html).

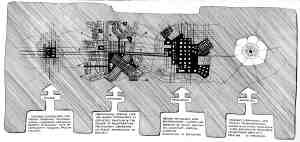

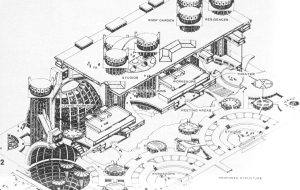

Soleri created thirty schemes based on theoretical propositions of arcology that were meant to be a guideline toward a new option, not a blueprint for a city-civilization. His one micro-experiment, Arcosanti, was meant to be a test of the arcological concept, realized. The goals of Arcosanti were to create a historically sound conception of the morphology of the city as an evolving organism, to test the conception through a verification process – transferring ideas into the actual construction of a micro-city –, and to proceed from beginning to end of the program in the manner of an open-ended process to be lived in and experienced by some thousands of apprentices and students. (“Arcology: The City in the Image of Man”, p. 131).

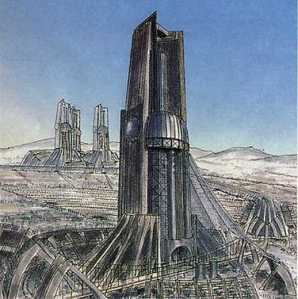

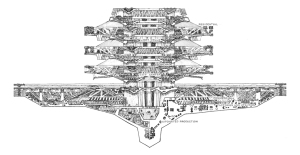

When looking at the different arcologies, there are a few design decisions that are noticed. In Babel City, the vertically stacked structure emphasizes the want to eliminate the use of the car. By stacking the structures, the distance needed to travel is shortened to a simple up and down movement. Also, living, working, and playing spaces are all intermingled within each other. This is to promote the social and community interactions that Soleri said sprawl eliminates. Though these spaces were dispersed closely throughout the project, the private spaces versus the community spaces are noticeable. The community spaces are more open and larger to allow for a lot of community interaction, and the private spaces are much smaller. This is probably due to the fact that Soleri wanted people to interact with one another.

Sign Outside Arcosanti

(http://cdn.volcom.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/ArcosantiSign.jpg)

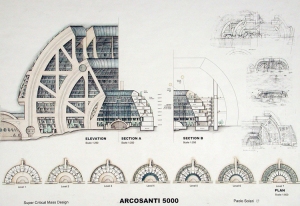

When looking at the original drawings of Arcosanti, one can notice all the ideas and concepts of arcology within the design. One of the main ideas apparent in Arcosanti is the paradigm of complexity, miniaturization, and duration. “Complexity; the many events and processes that cluster wherever a living process is going on. Miniaturization; the nature of complexity demands the rigorous utilization of all resources so miniaturization is mandated and a part of the process. Duration; Living outside of time – process” (“Arcosanti: an urban laboratory,” p 11). Using these three parameters, Arcosanti as a community meant to be a living organism, succeeds by constantly improving itself. It never becomes something that is obsolete. “Since we advocate frugality, we are automatically on the other side of ‘planned obsolescence’ and averse to the national megagarbage dynamic” (“Arcosanti: an urban laboratory,” p. 51).

In regards to sprawl, the project is dedicated, by intent and design, to the notion of containment as opposed to the recent notion of diaspora; with the automobile being the main protagonist. This is seen through the compact design and the tiers of structure, one on top of the other, to create an urban environment with no need of the automobile. Also seen in Arcosanti’s structure is a mindfulness of the waste inherent in diaspora because of this compact design. The hemispherical structures, or apses, are used as passive solar design techniques to save energy. These were seen and used in his earlier project, Cosanti. They are primarily southern facing in his new plan but east/west facing in his old plan. The reasoning behind the south facing apses is to allow light to enter the space when the sun is lower in the winter, and to create shaded space when the sun is higher in the summer. Since Arcosanti was primarily for students and apprentices, the rooms are relatively small and the program spaces deal with that kind of community. There is a theater, workshops, studios, residences, meeting areas, and other social programs included. “To integrate living, learning, and working is one of the main goals of the project. The results and the consequences could be momentous. It could mean the reshaping of a whole landscape and the culture of such landscaping supports” (“Arcosanti: an urban laboratory,” p 32). This design really relates back to the word “ecology.” The spaces create relationships between living beings and their environment.

In a conversation with Soleri in May of 2007, Michel Sarda, President of the Art Renaissance Initiative, questioned Soleri on his concept of arcology and the urban laboratory, Arcosanti. He states, “Some might even say that, like in the military, spreading out creates a better protection than having a larger concentration,” to which Soleri responded, “If we gear the importance and nobility of life on the fact that living together makes us more vulnerable to an atomic warfare, then we really are at the bottom of the barrel. The very first priority is to get rid of atomic warfare” (“The Mind Garden”, p.124). Soleri believes that this spreading out is what paralyzes us as a nation. We become isolated and it takes more resources and energy to obtain resources and energy as a sprawled nation. He believes this three dimensional “container” is the solution to all the problems relating to sprawl; economically AND socially. Michel Sarda asks later on in the conversation about the “container”, “Isn’t the container also a boundary?” Soleri replies, “No, a container is not segregation, it creates the possibility for small elements of life not only to survive and exist, but to be in contact with other small elements of life” (“The Mind Garden”, p. 125). This is the ecology coming out of arcology. The way humans interact with their environments. It does not isolate people from one another, it brings them into contact with one another where the sprawled city does not. As stated in the first paragraph, sprawl also had to deal with the concept of private property ownership. Soleri’s concept of arcology eliminated the idea of private property because it was too isolated. Sarda states, “Arcosanti… challenges paramount American values such as private property or the role of the automobile as a symbol of freedom.” Soleri responded, “I am not against private property. I am against the creed that makes private property the iconic solution to all problems facing the human species… Arcosanti is first and foremost, a laboratory. I repeat, a laboratory.” (“The Mind Garden”, p. 127,130). He was right, it is just a laboratory; an experiment to test the concepts of arcology in a real-life situation and setting.

“He dreamed of buildings and people interacting as a ‘highly evolved being.’ The sun would warm them and the breeze would cool them. Nature would surround them. The buildings would soar, reaching toward the sky with small apartments and large public spaces” (http://www.azcentral.com/news/articles/2010/08/22/20100822arcosanti-paolo-soleri.html). Soleri advocated for community and conservation. He wanted to save the planet and humanity. A society based on “hyperconsumerism,” he said, could not be sustained. Soleri built Arcosanti as a remedy to this “hyperconsumerism.” It would be his experiment of thousands of people living together to teach the world how to grow. This is why he considers Arcosanti to be his laboratory. He did not mean it as a blueprint or physical solution to changing cities, only as a reference point to change the structure and the way society imagines cities. Soleri was hailed as a futurist. In 1976, Newsweek magazine exclaimed, “As urban architecture, Arcosanti is probably the most important experiment undertaken in our lifetime” (http://www.azcentral.com/news/articles/2010/08/22/20100822arcosanti-paolo-soleri.html).

There are many speculations as to how arcologies would be able to sustain population growth. Paolo Soleri does not write or comment about this topic. This may be because he never had to encounter the issue of population growth, or he expected people to move to other arcologies as they grew older. One website, http://en.citizendium.org/wiki/Arcology, though not a credible source, submits an idea of what they think Soleri could have meant with his arcologies in response to population growth. “Arcologies do not to be singular, monolithic structures, as commonly seen in a lot of fiction. Smaller arcologies are designed to support a small population, but can link together by linking smaller related arcologies, creating a ‘compartamentalized’ arcology. A single-building arcology could support the population of a small town (5,000), and additional five-thousand-person arcologies could be built later in neighboring lots, effectively creating a ten-thousand, fifteen-thousand, or larger arcology. The current limit of human technology and arcology design could, in theory, fit the entire population of Earth (c. 6 billion people) into an area no larger than Louisiana” (http://en.citizendium.org/wiki/Arcology). This way of modular building as a means of controlling population is further reinforced when Soleri states, “The material presented here is a schematic reference to modular urban systems that find full coherence as appendices and as origins of the urban rivers, carriers of the bulk of civilization” (Arcology: The City in the Image of Man, p.10). These “rivers” suggest that there could be many arcologies along a network system of communication and transportation and these modular arcologies would control the population.

Image of Hyperbuilding arcology done by Paolo Soleri.

(http://utopies.skynetblogs.be/archive/2009/02/15/paolo-soleri-arcology-babel-et-hyperbuilding.html)

In terms of the successes and failures of arcologies, there really is no way to determine whether or not it would have failed since no arcology was completely built. Michael Graves, a retired professor from Princeton, says that it is more interesting than important. “’He took a position of living in his very special dream,’ Graves said. But Arcosanti was too remote, he said, literally and figuratively. Was Soleri ever influential? ‘No, to nobody,’ Graves said. ‘He was never able to mainstream anything, and you have to be, to be influential. People have to see it’ (http://www.azcentral.com/news/articles/2010/08/22/20100822arcosanti-paolo-soleri.html#ixzz2n1ogGVpP). This quote says a lot about the way people have thought about Soleri. It could be that he was not well known and people didn’t understand the importance of re-inventing the city.

“Twenty years ago I proposed that physical, emotional, racial and functional segregation were a greater evil than waste, pollution and environmental destruction. I think that I was on target then and that I am now,” said Soleri. Some of his most ambitious Arcology models, designed to accommodate up to a half-million people in vertical cities, would retain pedestrian accessibility, completely autonomous ecological support systems and social cultural centers that promote human interaction and belonging. Soleri is quick to blame the automobile for the urban sprawl he so abhors. In fact, he contends it is the value that we place on material possessions, including our cars, that has brought us to the environmental crisis we face. “Somehow, after 200 years, we have become hyper consumers possessed by materialism, buying our happiness,” said Soleri, who repeatedly expressed concerns that the waste we create will have catastrophic results unless we begin to change our way of life. He asserts that our automobile culture has caused us to move away from what is most important. “It has segregated our communities, wasted our resources and moved us away from the glory of culture, which should be appreciated as a great miracle.” (http://azgreenmagazine.com/wordpress/2013/04/genius-of-archology-paolo-soleri/)

Materialism and the constant need of the automobile to get anywhere could be the reason for the lack of interest in Soleri’s arcologies.

Today, Arcosanti still sits 70 miles north of Phoenix, Arizona and has a newly revamped master plan called Arcosanti 5000. With the passing of Paolo Soleri in April of 2013, it may only be left as it exists today, though society has changed since the 1970s, when Arcosanti was just starting out. The sustainability movement in response to the economic crisis is becoming more and more accepted by people all across the nation. Paolo Soleri was always skeptical of this sustainable movement. His website states, “Paolo Soleri calls what is happening in today’s green movement, reformation. We put solar panels on a single family home but can’t change the impact of inefficient construction or the consumption inherent to moving around the suburbs. We buy hybrid cars but must drive in the gridlocks of daily commutes. We buy ‘green washed’ products but continue the same hyper consumption that sprawl mandates. These improvements produce a ‘better kind of wrongness’” (http://arcosanti.org/Arcology). He believes that instead of reformation, we need to rethink the way we live and redesign habitats that solve the root of the problem, not just prolong the inevitable.

“Come to visit. Come and help. Please buy a bell.”

– Paolo Soleri

Works Cited

“Arcology.” Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arcology (accessed November 23, 2013).

“Arcology.” – encyclopedia article. http://en.citizendium.org/wiki/Arcology (accessed December 9, 2013).

“Arcosanti – An Urban Laboratory in the Arizona Desert..” INTRODUCTION TO ARCOLOGY. http://arcosanti.org/Arcology (accessed November 22, 2013).

“Arcosanti – An Urban Laboratory in the Arizona Desert..” Arcosanti Master Plan. http://arcosanti.org/node/10137 (accessed November 23, 2013).

“Arcosanti – An Urban Laboratory in the Arizona Desert..” Biography. http://arcosanti.org/node/7379 (accessed November 23, 2013).

Blueprint for the future. DVD. Directed by David S. Mayne. Portland, Or.: Very Sirius Productions, 2009.

Faherty, John. “Arcosanti, Paolo Soleri still inspire architecture.” Arcosanti, Paolo Soleri still inspire architecture. http://www.azcentral.com/news/articles/2010/08/22/20100822arcosanti-paolo-soleri.html (accessed December 9, 2013).

“Genius of Archology: Remembering Paolo Soleri.” AZGREEN MAGAZINE RSS. http://azgreenmagazine.com/wordpress/2013/04/genius-of-archology-paolo-soleri/ (accessed December 9, 2013).

Lima, Antonietta Iolanda. Soleri: architecture as human ecology. New York, N.Y.: Monacelli Press, 2003.

Sarda, Michel F.. The mind garden: conversations with Paolo Soleri II. Phoenix, Ariz.: Bridgewood Press, 2007.

Soleri, Paolo. Arcology, the city in the image of man. 4th ed. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 1969.

Soleri, Paolo. Arcosanti: an urban laboratory?. 3rd ed. San Diego, Calif.: Avant Books, 19841983.

Pingback: Organicism through Arcology, Biomimicry, and Sustainable Design | Organicism in Contemporary Architecture